"Really? The nation state is the hill you want to die on?" Safia Elhillo on HOME IS NOT A COUNTRY

wust el-balad #7

Anyone who’s spoken with me for more than 5 minutes about poems knows that few poets writing in English have shaped my writing more than Safia. Coming across her work for the first time (about seven years ago now!!!) felt like a revelation. It was less that I didn’t feel confident about integrating music and Arabic into my poems until I saw how she did it, and it was more that it just…had not occurred to me that you could just do that. The idea that a poem did not have to be legible, or at least not in the exact same way, to every single reader was mind-blowing, as was the idea that one can be in conversation with a dead legendary musician their mom is obsessed with and make unbelievable poetry out of it. All my Abdel Halim poems are indebted to Safia.

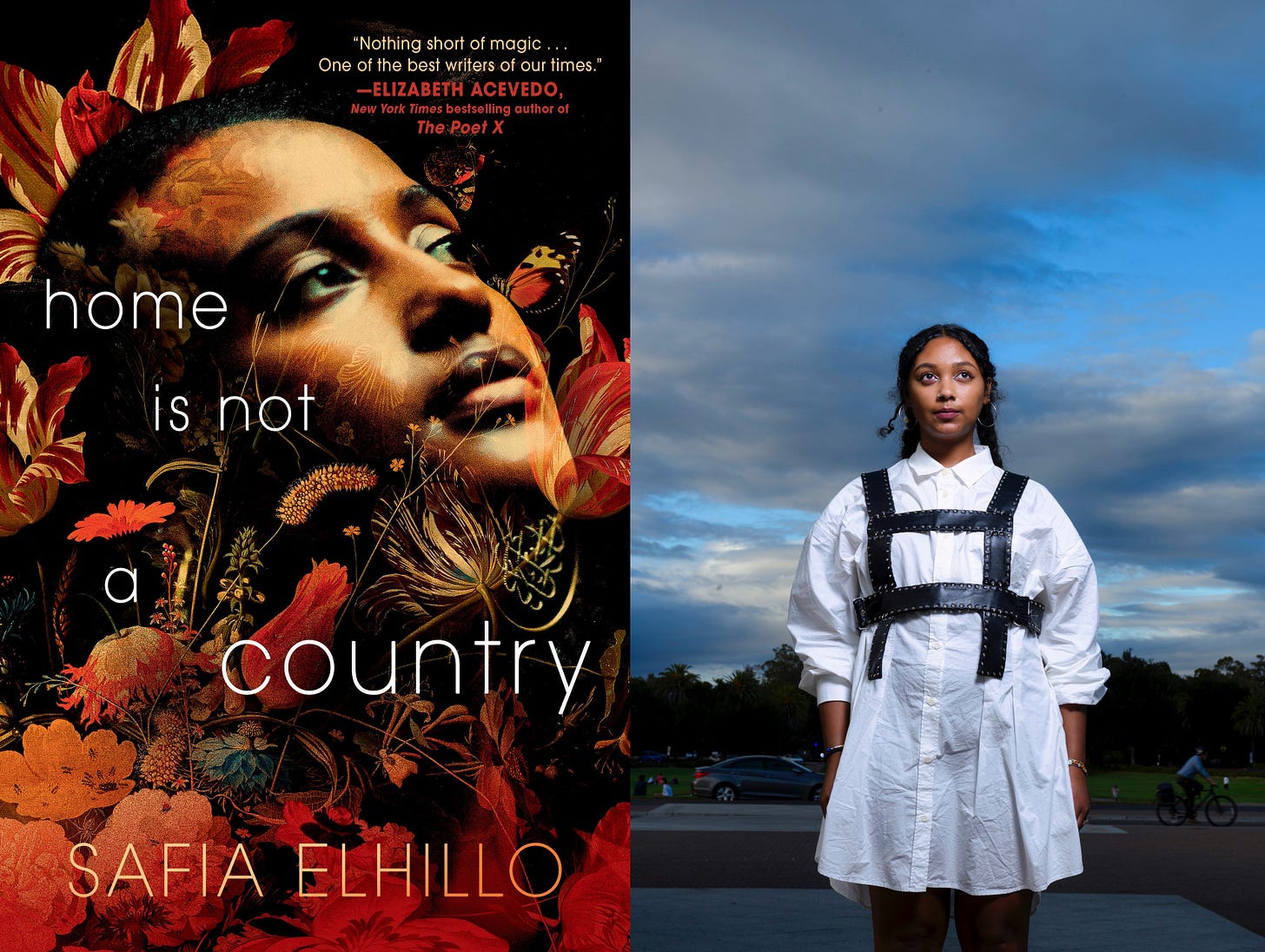

In honor of the paperback publication of Home Is Not a Country, her first YA novel-in-verse, I had the pleasure of speaking with Safia about nostalgia, nationalism, and genre—among other things. Below is an edited and condensed version of that conversation.

HAZEM: Do you have a preference between paperback and hardcover?

SAFIA: I have not yet seen the paperback, so I might revise my stance upon encountering it, but what I love about hardcover is that feeling when you take off the jacket and it just looks like a distinguished, old, engraved library book. It’s very pleasing to me. The jacket is also such a perfect little built-in bookmark so that I can stop using hair ties and receipts and bobby pins to mark my pages. I always feel like I have my life more together when I’m reading a hardcover. But I do like paperbacks because they’re lighter and more portable. In the before times, for example, I used to travel a lot, and I liked having several books on me at once. When you have a backpack full of hardcover books…that’s just a choice.

H: Nima is referred to in the book as a “nostalgia monster.” How would you describe your relationship with nostalgia? And how do you think writing this book has affected it?

S: The timing of my particular “nostalgia monster” era was a little different than Nima’s. It was between the ages of 21 through 27. When I was a teenager, I was really busy trying to be an American, and could not care less about anything else. I was lucky in that I did not, in my upbringing, have to go searching for identity. But that also meant that I really took it for granted. I grew up in a very Sudanese enclave in the D.C. metro area, and went to Sudanese school on Sundays. All my childhood friends are Sudanese. I didn’t feel any glaring absence of Sudaneseness in my life. If anything, it was a little too much.

And then I left to go to college, and I was just so excited to be a grown up by myself in New York—to not be surveilled. I wasn’t really spending a lot of time worrying about my identity as a Sudanese person because I was so excited to get to explore my identity as a poet and as a member of a poetry community. And then I started grad school and was deeply unhappy. It coincided with the first time in my life that I’d ever lived by myself; no roommates, no family, nothing. I was so lonely. Before that, I was always like: “it would be really nice if everyone left me alone for five seconds then I can hear myself think.” And then that wish came true, and I would go days at a time without speaking out loud.

I started to feel the distinct absence of all the stuff I’d always had in place to tell me who I was, that I didn’t even have to think about. It was the first time in my life that I felt this like distinct absence of my culture. I started trying to fill that chasm with listening to a lot of very old Arabic pop music, and watching Arab Idol. I’d also taken for granted just how frequently I had Arabic spoken to me growing up. I only found a Sudanese community in my last two seconds in New York. Before that, people weren’t really speaking Arabic to me. This is also a whole thing about race. There’re a gajillion Arabophone people in New York, but generally speaking, none of them would engage with me as a person in Arabic. No one would organically speak to me in Arabic. It go to a point where I wondered: “who knows if I can even speak Arabic anymore?” So I became less likely to initiate those conversations. All to say, the nostalgia wasn’t just for a “golden age” or whatever, but also for the very recent part of my life where all that stuff was so casual and I didn’t realize it.

H: As with most of your work, music plays a vital role in this book, particularly that of Sayed Khalifa. What do you see as the relationship between music and your poetics?

S: My poetics are really interested in memory; its failures and mysteries. For me, a song is like a container of the emotion I felt in the early days of encountering the song. It’s the quickest way to re-enter that emotion or moment. I usually write with music because it helps me hypnotize myself into that dream space. In generally, when I talk about, or refer to, music, it’s shorthand for me engaging with some sort of memory or feeling that’s frozen in a moment. Music does so much locating and contextual work. Economy in a poem is very important to me, so I love being able to create a landscape and a time period just by naming a song.

H: To you, what made this a novel-in-verse instead of a collection? And when did you know it was going to take that form?

S: I’m really attracted to hybrid forms. The novel-in-verse is a third space in between narrative and lyric. In terms of this being a Young Adult novel as well, adolescence is a space in between childhood and adulthood. And, of course, the experience being described in the book is a space in between a homeland and a hostland. Otherwise, I’d never written a novel before and it felt important that I enter this new form having my existing tools as a poet with me. I feel like I have the most handle on language when I’m writing in verse, so if I was going to learn something new and scary, like plot, I wasn’t also going to try and learn how to write in full sentences.

Language just feels a lot more malleable in a poem in a way that feels much more reflective of what language feels like inside my head; the texture of language before it is spoken. Since this novel is also written in first person and from the narrator’s interior space, I wanted to verbalize what it feels like to encounter the world from behind one’s eyeballs. Conventional prose didn’t feel right for that, I wanted it to be in little fragments, lowercase, and incisions to mimic how thoughts can just float across and disappear. Since my narrator is a young person who is obsessed with and tormented by language, I wanted the language itself to be a little tortured. That’s where the lowercase, the caesuras, and the bilingualism come in. It couldn’t just be clear, plain, punctuated, capitalized sentences. I wanted it to feel like the kind of language that exists on the tip of your tongue before it comes out.

H: What does the category YA mean to you?

S: When I started writing this book, I literally did not know. I thought: “is it just any book where the narrator is a young person?” I’d asked a friend of mine, and he said: “yes, it generally helps if the speaker is young, but there also can’t be a sense of jadedness.” So, for example, a YA novel can have sex in it, but sex can’t be unconsidered. There can be drugs in it, but they can’t be unconsidered. It has to feel like a big deal. It’s a coming-of-age story, so you’re arriving at the thing in real time. It can’t be casual.

In writing Nima, I was trying to hold on to this idea of a speaker who doesn’t already feel like they know everything. I wanted a speaker that we would watch ask questions and seek answers. And I think that is fundamentally what makes it YA, this deep wondering. The book itself is very wide-eyed.

H: That absolutely comes through in Nima’s curiosity, as well as in the ways in which she is frustrated; the way she gets mad at things not being explained to her—it’s a very relatable teen feeling. Speaking of which, one of the most powerful relationships in the novel is that between Nima and Yasmeen, who is revealed to be living, but without a body. Rather than fight her, Nima finds a way to have them both exist and they are reunited in real life later. Do you feel like you have had to struggle with a Yasmeen in your own life?

S: I literally was about to be named Yasmeen! And then in the 11th hour, my dad’s great-aunt Safia died, and my family wanted to honor her. I know name stuff is at the crux of “diaspora poetry” or whatever, but there is truly a particular curse to my name in that people get it wrong on both sides! The more common name in Sudan is Safia [Sa-fey-a] so people assume it’s that and then in English people just make whatever sound they want to make.

H: This is very true from my experience.

S: So the name Yasmeen wasn’t a lifelong obsession or anything, but it was this little piece of information that I’d deemed insignificant, except for it being a cuter name, but then when writing the book I started thinking about it as this alternate version of myself that I could flesh out. I knew her name. I knew where she lived. I knew what she’s like, and I knew what she’s done that I haven’t. She became a very particular part of my nostalgia monster era; a way of letting myself indulge in imagining an alternate reality in which I’d been given this other name, and I’d never come to the US and had been allowed to grow up deeply in context, and therefore all of the things that ail me would just magically disappear. It was also a way of telling myself: “it’s definitely not your own cursed brain chemicals, it’s just that you grew up in the wrong context.” Or: “you don’t need therapy; you just need a homeland in an alternate dimension.” That might honestly be cheaper than therapy.

H: In future work, do you think you’d want to try prose, or do you imagine you’ll be sticking to verse?

S: I’ve learned to never say never because I sure as hell never thought I’d write a novel, and that happened. But definitely not yet. There is a part of me that’s vaguely curious about writing essays. I think I would sooner do that, then try to write a novel in prose. The mechanics of the novel are just not what I feel fluent in. The whole thing with plot is that it’s cause and effect, which is just not how my brain and poems work. I exist from a place of lyric vibes. If I was trying to write plot and prose at the same, it would feel like trying to pat my head while rubbing my stomach. But I’m definitely open to it! This book broke the seal for me a little bit.

Another reason that I am more attached to poetry is how exploration is more baked into the medium. I was in a workshop with Louise Glück who told me that what my poems needed was for me to occasionally just look out the window. That might have been residual from slam, where it was so important to know what a poem “was about.” But I grew to learn that the unknown is such fertile space for poetry in a way that—I don’t want to make any absolute statements about fiction, but in a novel, I feel like there’s a responsibility to know what happens to all the people that you populate that world with. Personally, if I were to just end a story 75% of the way through and someone was like: “what happens to such and such person?” I’d say: “I don’t know!” That feels good to do in a poem, but it feels rude in a novel. In the literary world I come from, endings are not concrete.

H: Like much of your work, the book features a lot of sentences in untransliterated Arabic. What do you see as the importance of not just including Arabic, but the Arabic in the original text in your writing?

S: I’m always thinking a lot about language, and more specifically the relationship between English and Arabic. In the very early poems I was writing, I made one attempt at transliteration and it was just…ugly. It didn’t actually make the sounds in my head. It wasn’t creating any music. In trying to transport it from one side to the other, I ended up hurting it, so I decided to just leave it intact. If that makes the poem less readable to a non-Arabic reader, that’s okay. I like to think that there are many different versions of a poem available within itself. There’s a reading for someone who understands both English and Arabic, and has context for my particular intersections and cultural markers. And then there’s the version for the reader who only reads and understands English, and I think that version is intended to “work” as well.

But if it doesn’t, then sorry. That’s just lower on my list of priorities. All my poems— this novel—are written for a very particular reader, and I really only have the bandwidth to care for that particular reader. My hope is that everyone else is experiencing what it’s like to eavesdrop on a very interesting conversation.

H: In your future work, do you feel like you’ll return to the theme of nostalgia, or does that feel done?

S: I feel like I’m definitely, at least for the time being, exorcised of it. I gave it two books worth of real estate, and now I feel ready to move on. I’ve always worked from a place of obsession, and I don’t really know how to spend time working on something if I’m not totally obsessed with it. And I think this particular obsession has run its course.

I’m glad I went through it though because I needed to articulate those questions of nationhood and community for myself, otherwise I might have still been caught up in the same “nostalgia monster” era in my 30s. I had to let myself indulge in that feeling so I can come out of it asking myself: “really? The nation state is the hill you want to die on?” Now that I feel very held and very contextualized in my community, and have that feeling that I belong to whom I belong to—it feels enough. It’s fine. My brother has this recurring joke that all my friends can be categorized as either artists or Sudanese people. I’m not lonely in my tower. I feel very lucky to be in community with so many hyphenated Sudanese people.

H: There came a point in my life where I had to sit down with my writing, all the “my country TM” poems, and say: “the state will not save you. Please think of community beyond citizenship.”

S: No, exactly. Personally, I have enough iterations of Sudaneseness for me to absolve myself of this idea that there’s one “correct” way to be Sudanese.

Sudanese by way of Washington, DC, Safia Elhillo is the author of The January Children (University of Nebraska Press, 2017), which received the Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets and an Arab American Book Award, Girls That Never Die (One World/Random House, 2022), and the novel in verse Home Is Not a Country (Make Me A World/Random House, 2021), which was longlisted for the National Book Award and received a Coretta Scott King Book Award Author Honor. With Fatimah Asghar, she is co-editor of the anthology Halal If You Hear Me (Haymarket Books, 2019). She is the recipient of a Wallace Stegner Fellowship from Stanford University, a Cave Canem Fellowship, and a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from The Poetry Foundation. Her work has appeared in POETRY, The Atlantic, and The Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day series, among others, and has been translated into several languages.

Hazem Fahmy is a writer and critic from Cairo. You can find his work here and follow him on social media here.

Home Is Not a Country is out now from Penguin Random House. You can find it here, as well as in local bookstores and libraries across the US.