"Get this emotion out of this language!" Melissa Lozada-Oliva on DREAMING OF YOU

wust el-balad #1

Not long into Melissa Lozada-Oliva’s brilliant novel-in-verse, Dreaming of You, the speaker casually remarks: “New York is cool, because you only start / dating someone so that it’s easier to pay the rent.” As a recent transplant to the city, one who is still very much learning to not sob at the grocery store remembering how much things cost in Texas, this line made me laugh. Then it made me sad. Then it made me laugh again.

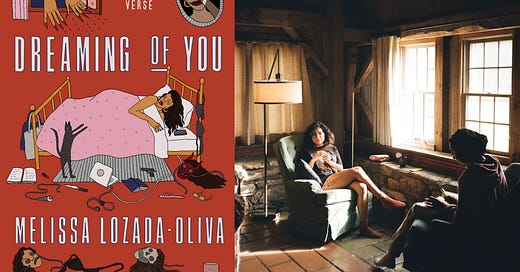

The whole book is a whirlwind; at once tragic and hilarious, as fantastical as it is a bitter reflection of our profoundly unhealthy relationship to celebrity and cultural capital. On a personal level, the book also happened to be the first of the recent boom of novels-in-verse that I’ve read. Though I’d been eager to explore them, I often wondered what, beyond the marketing, such a form would be capable of doing. It’s such a delight to have your skepticism eviscerated by a good book. An even bigger one to get to speak to the author after putting it down. The following is a condensed and edited version of that conversation.

HAZEM: In terms of the format, did you feel like the book being a novel-in-verse unlocked something you wouldn't have been able to do in a “regular” full-length collection of poems?

MELISSA: Yeah! I was initially so stubborn about this not being a novel-in-verse. It just sounded corny to me. At NYU, I had this class where we were studying people's first books. It made me think of what it takes, thematically, to put a good book of poetry together, and how to make it have an arc. I knew I wanted to tell a story, and the abstractness of a full-length was too hard for me. I ultimately found the novel-in-verse to be more freeing.

H: I hear you on the deep anxiety of trying to put together a full-length, especially a first one. Sometimes you think to yourself: “these are poems. They're relevant to each other. I don't know what else to tell you.”

M: I think so, too. Especially if you write some things together in a specific span of time...they're all gonna have to do something with each other; the theme of your life at the moment.

H: I was really struck by the wonderfully diverse and robust use of form in the book. Poets sometimes joke about how anything can be a form. What is your approach to using form? How does it come to you as you’re writing?

M: Because I come from this slam [poetry] background, I used to think I was “anti-form,” like it would put me in a box. But it turns out going to poem school was very helpful in showing me that form can be informative to what you’re trying to say. You often, actually, need boxes and rules to squeeze out what you’re trying to say.

For example, I love doing sonnets as a dialogue between two people getting to know each other—which is throughout a lot of the book because, well, there is a constraint when you’re falling in love with somebody. It’s extremely awkward!

Form is so fun for me. I don’t think I’ll ever stop being experimental. I like to play around and to think of forms less as a thing telling me what to wear and more as an opportunity to chose from all these outfits.

H: Speaking of ways to mess around on the page, one of the things I found very compelling about the book was the way it uses persona poems—especially since there is also speaker and character named Melissa. How do you think the novel-in-verse format shaped your use of the “I” in these poems?

M: I definitely played a lot more with it in this book than in other work. In general, I feel like once we write a poem it is no longer ours. It grows. This is especially the case if you write a poem about somebody else, and there is both an “I” and a “you” in the poem. That will forever be its own thing because anybody who reads it will interpret themselves in the “I” and think of their own use. It’s just…no longer yours.

H: When poets use “you,” it can sometimes be addressed to a specific person, including the self, but can also be this universal, effervescent “you.” Which kind of “you” do you gravitate towards?

M: With this book, the poems addressed to the “you” were a process of me dealing with a time when I was so terribly in love and waiting for somebody to acknowledge that they love me back. So when I was writing these “you” poems, it was like a pleading: “please see me. Look at me. Be the ‘you’ of my life.” Then it also becomes a kind of prayer, like making someone into a small god they aren’t.

I’m still writing “you” poems. They’re hard, but they make you say everything you want to say without actually texting someone or saying it to their face.

H: Love is such a poignant theme in the book. I really liked how much the speaker skewers the idea of being in love and in New York by constantly referencing how expensive the city is. How has the material reality of living in the city affected how you see it?

M: There’s obviously this myth to New York and romance in New York. And honestly I am in love with it. There are phases to it. There’s a New York that you’re imagining before you move here. Then there’s the initial euphoria of being here. Then all of a sudden it’s winter, and you’re just fucking crushed and lonely. But New York is romantic when you let yourself become a part of it. Part of this book was exploring this feeling of finally being entangled with the city, and seeing all of the ugly parts of it, too.

H: As an Arabic speaker, it’s really exciting for me to see poetry in English that embraces the exclamation point. So many writers in English are so weird about it. It’s almost shamed out of a lot of young people who formally learn how to write in English. When you were working on the book and showing it to people, did you feel a tension there at all?

M: Yeah, people are still weird about the exclamation point! For me, a period is so final and severe. I’m just very enthusiastic. Also, it’s sexist to be like: “get this emotion out of this language!” Punctuation can do so much, and it can be so funny and useful. It can really show the weird idiosyncrasies of different characters.

H: The book very consistently interrogates the ways in which identity has become commodified in literature over the last decade. I’m very grateful for my time in slam, but I also always like to ask poets who came from that scene: to what degree do you think the competitive format contributed to that commodification?

M: I’m also very grateful for my time in slam because it just showed me that I can do whatever I want. It showed me that poems can be alive and tell stories. That said, it was kind of fucked up that we were baring our souls in these really complicated, unfinished thoughts about identity for points that could maybe one day lead to money, or a viral video—which could also lead to money. The whole concept of slam itself is really tied to capital. Yes, it started out as a fun bar game. But then it becomes serious once people start getting careers out of it.

The poems that have gone viral for me all have to do with my identity as a Latina, and as a woman. I was able to speak to colleges because of that. But I also did these things for companies that I didn’t really want to do when I was in a hard place. One time, there was this fax company who was like: “We really like your poem, ‘My Spanish,’ but could you make it more positive? And more of an anthem? We’re trying to recruit Latino workers.” I almost did it! But it felt really shitty to be a writer making money only because someone wants to sell fax machines.

Also, I think when we were in slam—it was a strange time because that trajectory, going viral on social media, was possible. There was this three-year period were that could happen to you. But then the videos stopped getting posted. I don’t even know if it’s slam in particular even. It’s more so the specific nature of our relationship with social media and technology in the mid-2010s.

H: I’m also really interested in the book’s approach to the idea of celebrity itself. Selena is first mentioned in the narrative in the context of the speaker’s family, and their dependence on her music to fill the awkward silences in their home. At some point, the speaker even plainly asks: “will we ever stop crying about the dead star?” Building off of that, do you think we look for too much from celebrities?

M: Damn, I think we do. We ask too much of celebrity. Of course, I do think the amount of visibility they get comes with a certain amount of responsibility—especially now, when celebrities can have social media and can respond directly to us.

I was listening to the podcast You’re Wrong About, and they have a five-episode thing on Princess Diana. They talk about how fame and the royal family are—and this is complicated wording—“like prison” in the sense that their world becomes a lot more closed because they can’t be invisible.

I thought I would grow out of the desire to be famous, and I think I kind of have. But I also really like being validated, and I like recognition. But also, I’ve seen the psychologically fucked-up things fame can do to people. And I know it can be very lonely for some. And it can make people feel paranoid about everything that they’re going to say. Celebrities really are just people.

H: In the last poem of the book, “Selena Still Has Some Time Left,” do you think the speaker is ready to, or even capable of, letting her go?

M: I think that poem is definitely the letting-her-go poem. It’s really mournful because it is imagining this world where she was able to live out the full extent of her life and have a daughter and whatnot. That feels like closure. The book is a kind of love affair so we know it’s gonna end, but this poem invites you to see it all the way through to the end; another life where Selena grew old, has survived her mother, and even has tension with her daughter. This is the speaker letting that alternate reality go.

Melissa Lozada-Oliva is the child of Guatemalan and Colombian immigrants. She is the author of Peluda and Dreaming of You. She's been featured in Vogue, NPR, Vulture, BBC Mundo, and Oprah Daily. You can follow her at @ellomelissa everywhere except in real life.

Hazem Fahmy is a writer and critic from Cairo. You can find his work here and follow him on social media here.

Dreaming of You is out now by Astra Publishing House. You can find it here, as well as in your local bookstore and library.